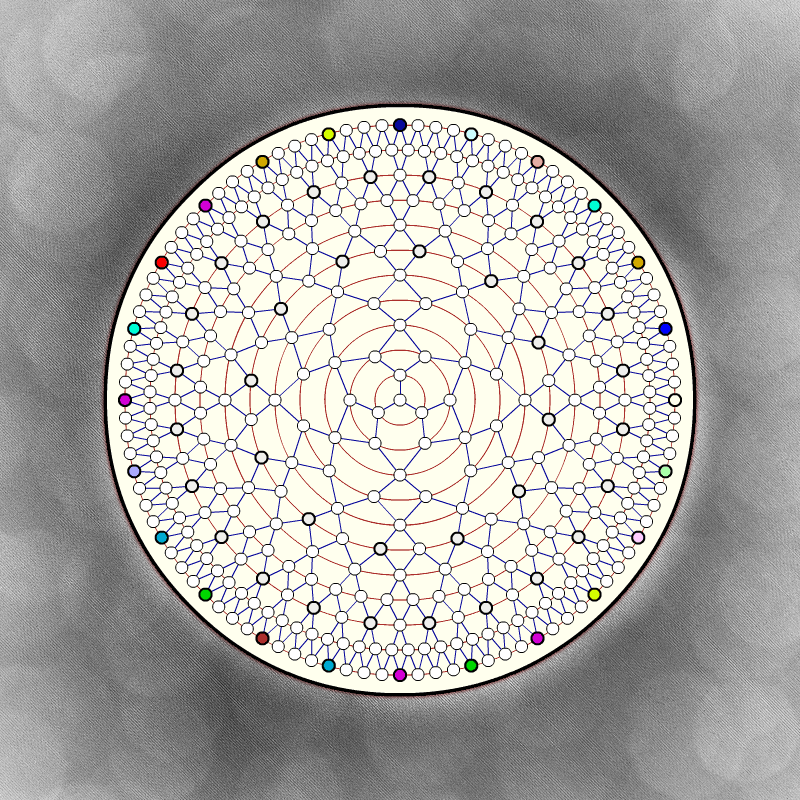

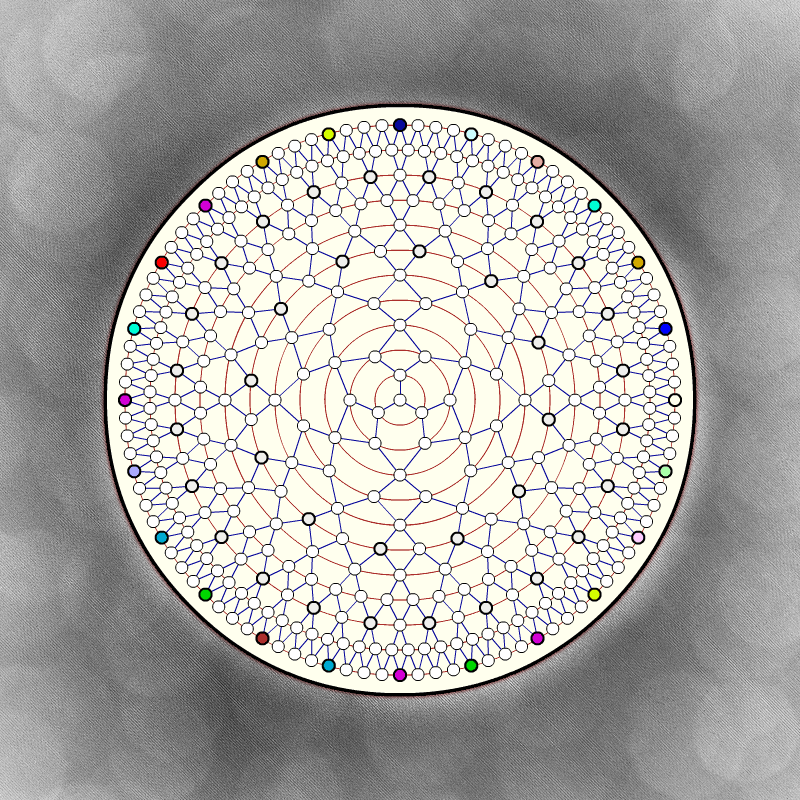

I’ve been digging through some old archives, and came across an old, old design of mine for a game called Implosion. The general idea was that it handles up to twenty-four (!!!) players, and can be scaled down to work with factors of twenty-four; so, twelve, eight, six, four, three, or two. The board is twelve concentric rings populated by a series of connected nodes, with the players’ starting nodes on the outer ring, and a single scoring node in the center. Each node can contain a number of units belonging to a player, and the further out the node is, the more it can hold – twelve for the ones on the outside, and only a single unit in the middle. Moving and attacking is very simple, and there are “spawn” nodes in the rings about two thirds and one third the way in to generate new units.

The game was originally designed to be played asynchronously online, over a long period. Say, one turn per hour, one hundred sixty eight turns over the course of a week. As the game goes on, the rings start disappearing from the outside in. The board implodes, one might even say. When a ring vanishes, all the units on those rings vanish as well, until the entire board disappears on the last turn, and the game is over. (Actually, that part isn’t in the original version of the rules, which I’ll post below, but I know that was part of the design from the beginning. Weird.)

Anyway, you can see that this is a relatively primitive game, and it would be ridiculously unwieldy to play on a regular board, and probably still clunky and kind of a drag to test out in an online multi-player setting, as well. But it still feels like it has potential, and I think that with some futzing about and iterating over a few rounds of playtesting, something neat could come out of it. I don’t have anywhere near the bandwidth to do any of that right now, but it struck me well enough to give it a little think again, and maybe set it to simmering on the back burner of my brain…

Here are the rules from the original text file; I’d seriously revise these before attempting to play, but for the sake of posterity, enjoy:

Implosion

The game is played by 24 players, on a board made of interconnected nodes in twelve concentric circles. Each player begins with twelve units on their starting node on the rim of the Implosion board. Moves are submitted over the course of a turn (maybe an hour, when played online), and are executed in the order received. A move consists of a player transferring one or more units from an occupied node to a node that is connected to it. Nodes are connected to anywhere between three and six other nodes on the board, and units may only move along these connections. If the target node is empty, or contains units owned by the moving player, the units just move into the new node. If there are units belonging to another player in the target node, it is considered an attack – a battle occurs, and the winner’s remaining units are placed in the node. Units owned by more than one player may never occupy the same node without conflict. Units may only be moved once per turn.

When a node containing one player’s units is attacked by units owned by another player, the conflict is resolved by unit-to-unit battle, until only the units belonging to one player remain. The defending units attack first, then the invading units, and continue back and forth as long as both sides have at least one unit remaining. When an attack is made, there is a 50% chance that the attacked units will lose a unit, regardless of the size of the attacking or defending forces. For example, Player A uses three units to attack a node which contains two units belonging to Player B. Player B goes first, and succeeds, so Player A’s attack force is now two units. Player A also makes a successful attack, bringing it down to two units against one unit. Player B’s next attack fails, but Player A’s attack in return succeeds again, clearing out the node. Player A now moves their remaining two units into the node. If another player has submitted an order to move units into the same node after Player A’s move, battle occurs again, this time with Player A playing the defender, and attacking first. Moves are resolved in this manner until all conflicts are resolved, at which point the moves for the next turn may be submitted.

A node’s capacity is determined by its distance from the center of the board. The outermost ring of nodes, the twelfth one out, may contain a maximum of twelve units per node. The nodes in eleventh ring out (second ring in) have a maximum capacity of eleven units, and so on, until the center “ring” is reached, which consists of a single node that may only hold one unit. There are four different kinds of nodes on the Implosion board – normal nodes, starting nodes, spawn nodes, and the center node. Normal nodes have no special qualities, beyond their regular maximium capacity limit. Spawn nodes are distributed around the seventh and tenth rings – if a spawn node is occupied by a player at the beginning of a turn, they receive an additional unit in that node (up to the normal limit for that node’s ring), before movement occurs. Starting nodes are where each player begins the game, and are considered to be spawn nodes, with the additional advantage of creating one new unit per turn even if the node is not occupied by one of the player’s units, unless another player has occupied the node themselves. The center node is the method by which points are scored – if a player occupies the center node with a single unit at the beginning of a turn, they receive a point. Needless to say, this is a very precarious position to hold.

A standard game of Implosion is played for 168 turns, or one week if the turns occur once per hour. A game may end early if there is only one player with units remaining, in which case, they are declared the winner. Otherwise, the player with the largest number of center points wins. Ties are broken by the number of units left at the end of the game, number of spawn points occupied, and, in extreme cases where two or more players have equal numbers of all of those measures, number of inner nodes occupied.